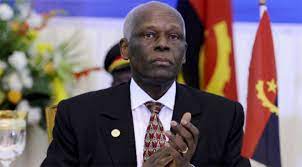

The UN Secretary-General António Guterres says he is saddened to learn of the passing of H. E. Mr. José Eduardo dos Santos, former President of the Republic of Angola. He was 79.

“As a member of the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola, José Eduardo dos Santos participated in the struggle that led to the independence of Angola.

“As President of Angola, he led the country through the signing of the peace agreement that put an end to the civil war in 2002.

“During his tenure, Angola became an important regional and international partner and advocate for multilateralism.

The Secretary-General presented his deep condolences to the former President’s family and to the Government and people of Angola.

Jose Eduardo Dos Santos, once one of Africa’s longest-serving rulers who during almost four decades as president of Angola fought the continent’s longest civil war and turned his country into a major oil producer as well as one of the world’s poorest and most corrupt nations, died Friday.

Dos Santos died at a clinic in Barcelona, Spain following a long illness, the Angolan government said in an announcement on its Facebook page.

The announcement said dos Santos was “a statesman of great historical scale who governed … the Angolan nation through very difficult times.”

Dos Santos had mostly lived in Barcelona since stepping down in 2017 and had been undergoing treatment there for health problems.

Angola’s current head of state, Joao Lourenco, announced five days of national mourning starting Saturday, when the country’s flag will fly at half-staff and public events are canceled.

Dos Santos came to power four years after Angola gained independence from Portugal and became enmeshed in the Cold War as a proxy battlefield.

His political journey spanned single-party Marxist rule in post-colonial years and a democratic system of government adopted in 2008. He voluntarily stepped down when his health began failing.

In public, dos Santos was unassuming and even appeared shy at times. But he was a shrewd operator behind the scenes.

He kept a tight grip on the 17th-century presidential palace in Luanda, the southern African country’s Atlantic capital, by distributing Angola’s wealth between his army generals and political rivals to ensure their loyalty.

He demoted anyone he perceived to be gaining a level of popularity that could threaten his command.

Dos Santos’ greatest foe for more than two decades was Jonas Savimbi, leader of the UNITA rebels whose post-independence guerrilla insurgency fought in the bush aimed to oust dos Santos’ Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola, or MPLA.

The MPLA had financial support from the Soviet Union and military support from Cuba in its war against UNITA. Savimbi was backed by the United States and South Africa.

The war would last, with brief periods of U.N.-brokered peace, until 2002 when the army finally tracked down Savimbi in eastern Angola and killed him.

Dos Santos abruptly shed his Marxist policies after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. He moved closer to Western countries, whose oil companies invested billions of dollars in mostly offshore exploration.